Bonsai, Bronze, and the Archive

This spring, Jim Dine’s practice unfolded across three distinct landscapes—each steeped in meaning, memory, and material exploration.

From the quiet precision of Portland’s bonsai gardens to the raw expanse of Baker City’s bronze foundry, and finally to Yale University’s storied halls, Jim continued his work across drawing, sculpture, print, and poetry. As ever, Jim’s work remains deeply rooted in process, curiosity, and poetics. In this newsletter, our chronicler of the studio, Olympe Racana-Weiler, shares highlights from Spring 2025.

Jim hand painting new sculpture in Baker City, Oregon.

This spring, Jim Dine goes to Portland, Oregon, to observe and draw a private collection of over one hundred bonsaï trees.

He had seen some of these examples last year at the city of Portland’s Japanese Garden. Stunned by the beauty of the bonsai trees, he spoke with the bonsai master, who explained that they require special care during the winter and spring to protect them from the cold and restore their shape.

These miniatures offered Dine the opportunity to explore and understand the life cycle of trees up close. Jim Dine chose two specimens from the Zen Garden collection. One was a hundred-year-old tree found in the frost, and the other was a cherry tree. He set up his easel, paper, and charcoal and began studying these amazing miniatures.

Bonsai studies; charcoal on paper. Portland, Oregon.

He then joined his team at the Blue Mountain Fine Art Foundry in Baker City, Oregon.

In 2005, Tyler Fouts established his foundry in the historic town of Baker City on the Oregon Trail, in the heart of the American West's desert landscape. Jim Dine and Tyler have been collaborating for thirty years.

Dine returned to the Baker City foundry to give the works produced there, a touch of his characteristic relationship with sculpture: color. This time, he painted a new cast of the sculpture “After the Flood”.

In Dine's work, the boundaries between sculpture and painting are constantly questioned. Since his early days, Dine has invited everyday objects to participate in the composition of his canvases, thus shifting the viewer's gaze outside the frame. The very texture of the paint is laden with rubble, sand, and mortar, bringing the pictorial surface closer to that of a bas-relief. The same encounter between different media occurs in his relationship with sculpture. Once completed, usually in plaster or wood, a figurative form emerges: Venus, Pinocchio, the heart. Then, found objects are often grafted onto the form, composing it or seeming to interact with it. When the bronze casting is complete, the relationship with color begins. Sometimes a traditional patina is used, but he often acts like a painter on his sculpture, completely redefining the reading of the form through polychromy. He determines a range of colors and then works freely on the different versions, giving them an almost unique character. This method, similar to that of printmaking, allows him to create variations and lyricism within the same form.

Jim Dine at work at the Blue Mountain Fine Art Foundry in Baker City, Oregon.

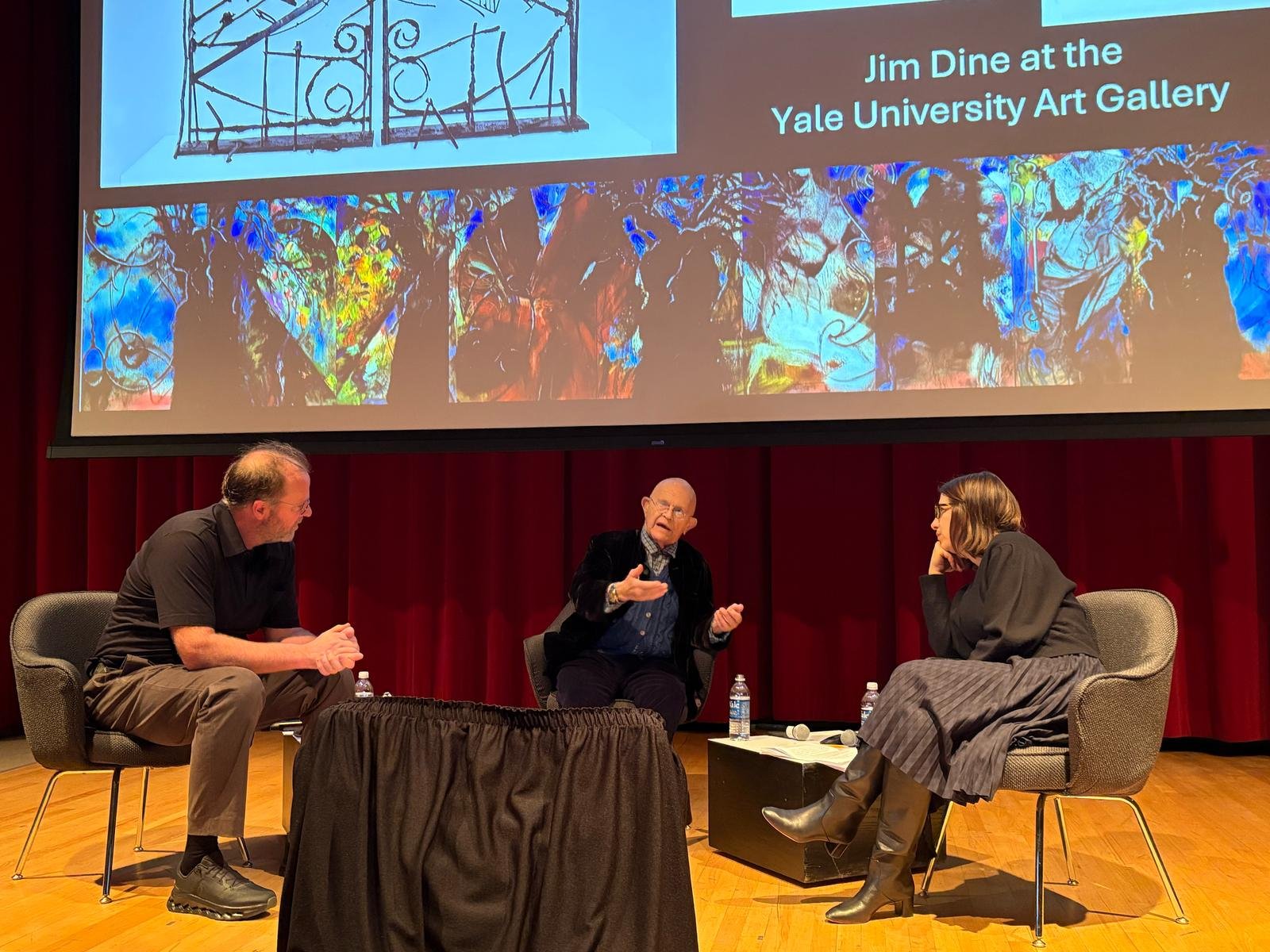

After his time in Baker City, Jim traveled to Yale University in Connecticut to give a lecture on the occasion of his exhibition “Jim Dine: “This is Me” ” at the Yale University Art Gallery.

Introduced by Stephanie Wiles, director of the Yale University Art Gallery, Jim Dine, Frida Spira, chief curator of the museum's paper, print, and photography department, and Daniel Clarke, artist and printer in charge of the Jim Dine studio, gathered to discuss the history and techniques of the works presented in the exhibition.

Jim Dine gives a lecture on the exhibition, “Jim Dine: This is Me” at Yale University Art Gallery, Connecticut. Seated left, Yale Alumnus Daniel Clarke (Jim’s assistant) and right, Freyda Spira.

Jim at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library with the original Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman.

Exhibition view, Jim Dine: “This Is Me” at Yale University Art Gallery, Connecticut.

Bringing together some thirty works, engravings and drawings, created around the world and by various printers, it was surprising to see a matrix used in a print as the central subject of the image, then to see it reappear partially or transformed in another edition. The discussion therefore focused on this method unique to Dine: never throw anything away, use the remnants of the past and give them a new life. This use of matrices as a formal archive to create a work is valid in all aspects of his work. It can be seen just as much in his relationship with writing. Dine writes constantly and everywhere. All his notes are then enlarged to be reworked. The word then becomes a visual object in its own right. He cuts it up and then pieces it back together. Dine composes the poem as a plastic form.

This trip was also an opportunity for Jim to see over one hundred of his poems and studies for them, enter the collection of the Beinecke Library at Yale University.